Jennifer’s Body (2009) is a film brimming with ambition, blending horror, satire, and coming-of-age drama into a sharp critique of power, sexuality, and friendship. Diablo Cody’s screenplay and Karyn Kusama’s direction work together to subvert some traditional horror tropes while attempting to craft a feminist narrative about transformation and survival. The result is a film that occasionally dazzles with its boldness but struggles to find its way. For all its provocative themes and clever moments, the film’s uneven tone and Cody’s dialogue create a disconnect that keeps it from fully realizing what it could have been.

Cody’s script is undeniably distinct. Her trademark wit and snappy dialogue, which defined her style in Juno, lend Jennifer’s Body an irreverent energy. Lines like Jennifer’s deadpan declaration, “I’m not even a backdoor virgin anymore,” are designed to shock while drawing laughs. The characters deliver their quippy remarks with Cody’s signature mix of pop culture references and sardonic humor, creating a heightened, almost stylized version of teenage speech.

But where this approach worked in Juno—a quirky, dialogue-driven comedy—Jennifer’s Body feels like an awkward fit. In the context of horror, Cody’s sharp, self-aware dialogue undermines the tension the genre thrives on. The characters often speak as though they’re detached from any stakes, and their hyper-verbal quips take precedence over emotional authenticity. Instead of feeling grounded in the film’s world, the characters come across as vehicles for Cody-cleverness. This creates a tonal dissonance that I find grating: the film wants to be both satirical and emotionally resonant, but the dialogue often prevents it from committing fully to either.

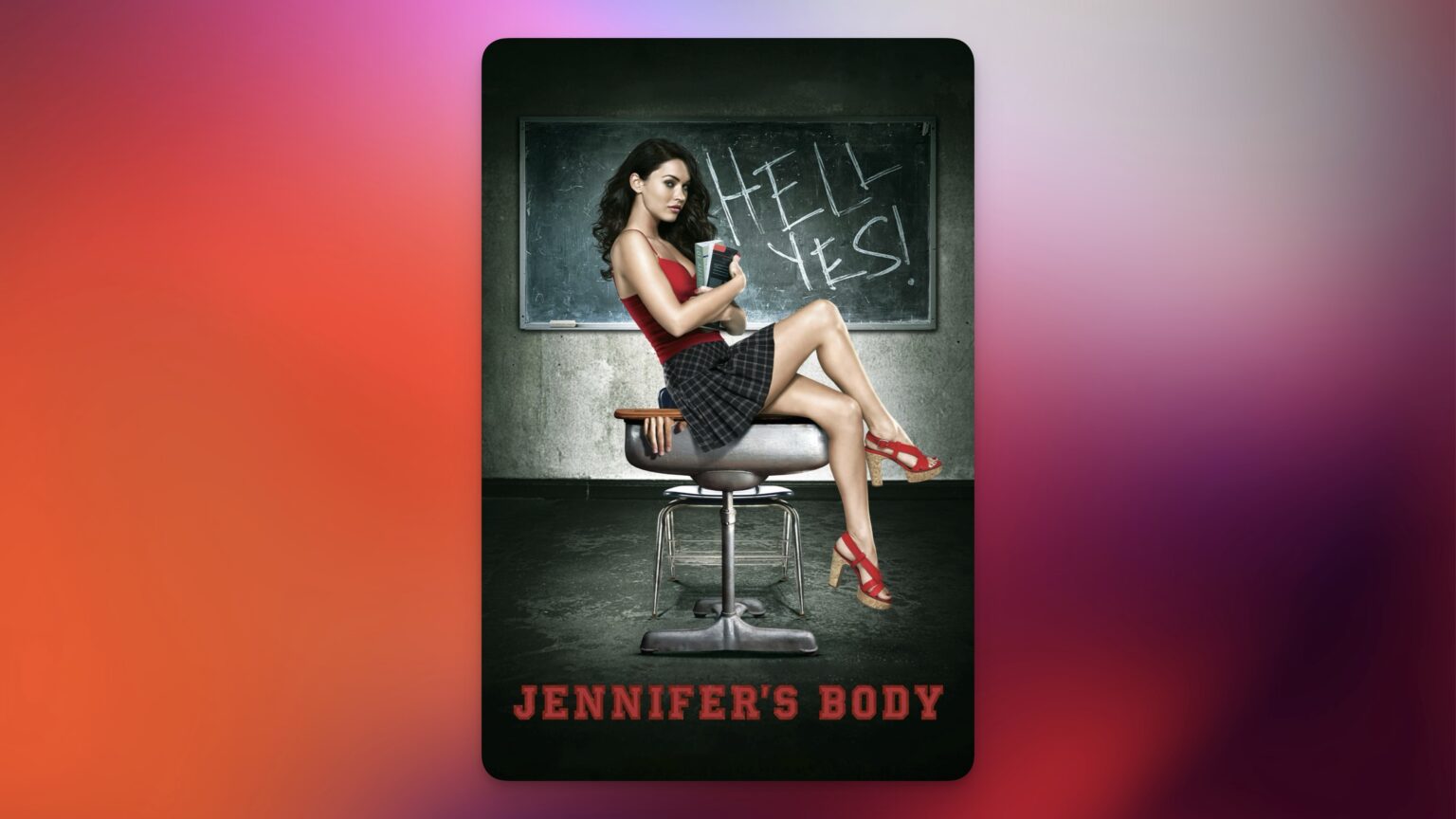

Take Jennifer, for example. Megan Fox delivers a fine performance, balancing the character’s predatory confidence with flashes of vulnerability. But the dialogue rarely gives her room to explore the emotional or psychological toll of her transformation. Jennifer’s descent into monstrosity is played for dark humor rather than genuine horror or pathos, which robs the story of its potential complexity. Similarly, Needy’s arc—from passive observer to empowered avenger—feels rushed, as her character spends more time reacting to Jennifer’s antics than grappling with her own inner conflict… right up to the moment she becomes a superhero.

The script’s insistence on being clever is especially apparent in its supporting characters. Chip, Needy’s boyfriend, is a placeholder for the “nice guy” archetype, with little personality beyond his sweetness and obliviousness. The male victims Jennifer lures are purposefully shallow, but their flatness makes them inconsequential rather than tragic. Even the villainous indie rock band Low Shoulder, while conceptually fun, comes across as more goofy than menacing. These characters exist to serve the plot, but they lack the texture needed to make the film’s horror elements land.

Cody’s dialogue works best in moments that lean fully into satire. Jennifer’s biting insults and her casual dismissal of societal norms—like when she describes the band as “agents of Satan with awesome haircuts”—highlight the film’s critique of how women are simultaneously idolized and objectified. Needy’s narration, I can’t stand it. It’s delivered with a mix of resigned humor and bitterness, and while I guess it captures the film’s tone of disillusionment, it reads like a capitulation to executives who don’t know how to watch movies, and have low opinions of their audiences.

The film’s cleverness often clashes with the story’s horror. The more self-aware the dialogue becomes, the harder it is to take the characters’ struggles seriously. In a scene where Jennifer vomits black goo in Needy’s kitchen, her quip, “I feel like boo-boo,” undercuts any of the visceral horror with a yearning to be as smart as a Whedon quip during peak Buffy. Similarly, the climactic confrontation between Jennifer and Needy loses some of its emotional weight because the dialogue prioritizes wit over raw intensity. By constantly reminding the audience of its own snark, the film keeps us at arm’s length from its characters.

The issue isn’t just one of tone; it’s also one of fit. Cody’s dialogue is inherently performative, drawing attention to itself in a way that feels out of step with the genre. Horror, even when blended with comedy, benefits from dialogue that feels natural and unforced. The best horror-comedies—like Shaun of the Dead or Scream—balance humor and tension because their characters’ speech feels grounded in their reality, even when the situations are absurd. Jennifer’s Body, by contrast, often feels like it’s winking at the audience, reminding us that we’re watching a script rather than inhabiting a world.

This disconnect makes it harder to invest in the film’s deeper themes. Jennifer’s transformation is a clear metaphor for the objectification and exploitation of women, while Needy’s journey represents a reclamation of agency. These ideas are powerful, but the film doesn’t truly explore them because the characters never feel real enough to carry that weight. The dialogue, while entertaining, keeps the story operating on a surface level.

Despite its flaws, Jennifer’s Body remains an ambitious and fascinating film. Cody and Kusama deserve a raft of credit for playing with horror tropes and crafting a story that centers on female relationships and empowerment. The film’s critique of exploitation—embodied by the band’s sacrifice of Jennifer and the marketing’s reduction of the film to Megan Fox’s sex appeal—feels especially relevant today. Moments of brilliance shine through, particularly in the exploration of Jennifer and Needy’s toxic, codependent friendship.

But those moments are buried under the weight of a script that feels misaligned with the genre. Cody’s dialogue doesn’t lend itself to horror’s emotional intensity, leaving the film feeling uneven and, at times, hollow. What might have been a groundbreaking feminist horror-comedy instead feels like an intriguing experiment that doesn’t quite stick the landing.