There is a moment in Thunderball—a flash, really—where you can see the franchise slipping just beyond its own grasp. It happens underwater, of course, because everything in Thunderball happens underwater. Sean Connery’s Bond, the embodiment of effortless cool, is flailing slightly, engaged in one of those extended, balletic combat sequences that seem to stretch beyond time itself. The choreography is mesmerizing, but it’s also sluggish, overlong. The pace, the tension, the momentum—all things Goldfinger had done more adeptly a year earlier—are somehow lost in the murky blue.

This is the paradox of Thunderball: a film that is both quintessential Bond and, in some ways, a mark of the franchise’s slow drift into self-parody.

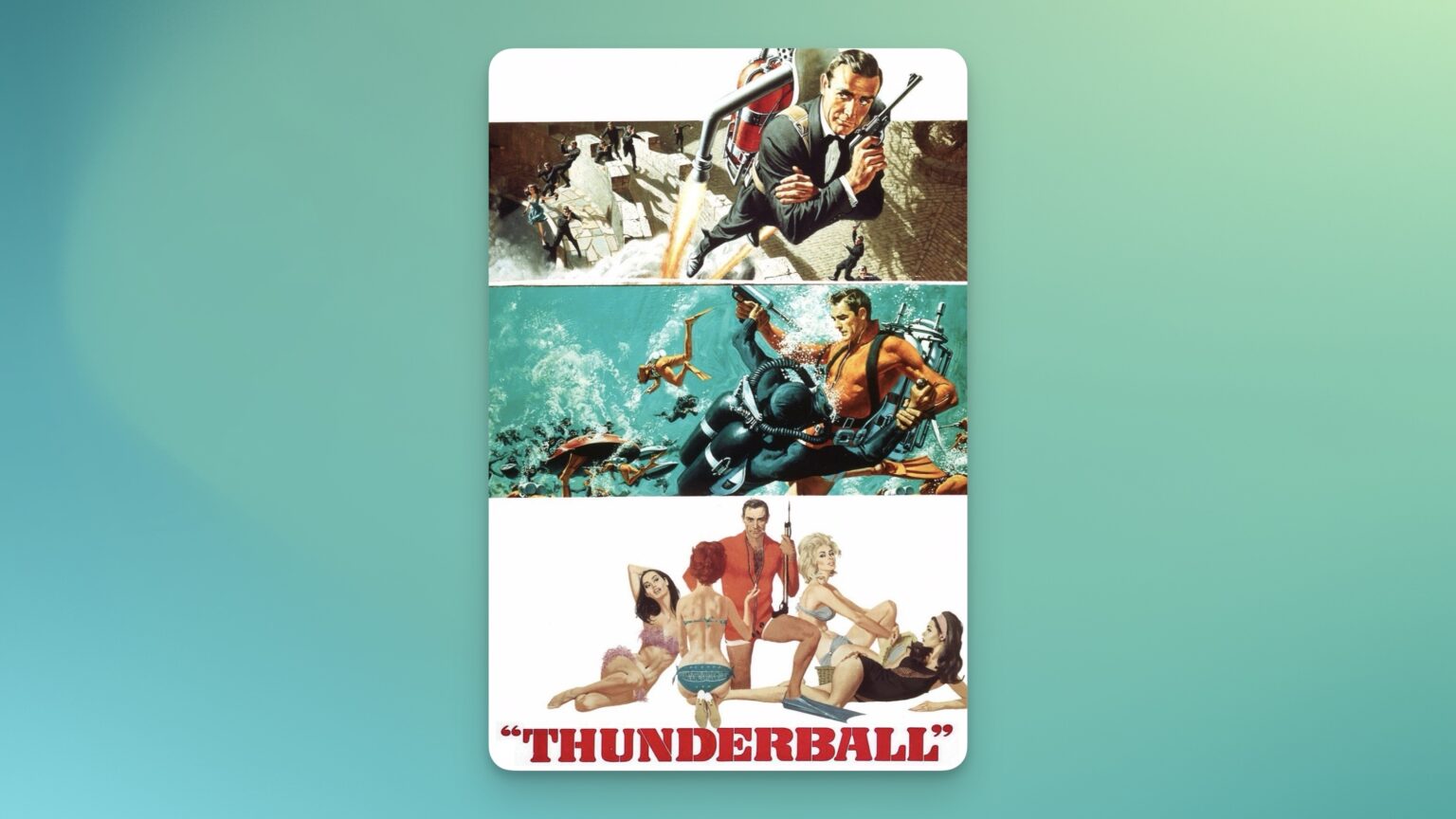

By 1965, Bond was no longer just a film series; it was a phenomenon. Goldfinger had turned 007 into a cultural juggernaut, and Thunderball arrived with the weight of expectation. The budget was massive—larger than the first three films combined. The action was grander, the gadgets more elaborate, the stakes higher. Even the title seemed to promise something explosive, something immense.

And yet, watching it now, Thunderball feels strangely bloated. The plot—SPECTRE’s theft of two nuclear warheads and Bond’s race to recover them—has all the makings of a classic spy thriller. But the film is obsessed with its own spectacle, stretching sequences past their breaking point. The underwater battles, objectively cool—and revolutionary in their day—now feel like beautifully shot exercises in patience.

Connery, to his credit, is still magnetic. This is his fourth outing as Bond, and he wears the role as comfortably as a tailored tuxedo. But there are signs of fatigue. The charm is there, sharp as ever, but the enthusiasm is waning. The film’s indulgences—its languid pacing, its fixation on style over substance—seem to weigh on him.

And then there’s the treatment of women, which even by Bond standards, feels particularly egregious here. The “seduction” of a physiotherapist at a health clinic is not played for romance, or even for the usual winking charm—it’s coercion, full stop. The film is full of these moments, relics of an era that has not aged well.

This is where my personal relationship with Bond films complicates things. I don’t love them. I like them well enough, and I have fond memories of watching them in the theater with my dad, but they haven’t aged well in just about any regard. And in the struggle with this script, I have to admit: I think I prefer the off-brand Bond, Never Say Never Again, to Thunderball.

This is not to say Thunderball is without its joys. It is, after all, a Bond film. There are high points: the thrilling opening sequence, featuring the now-iconic jetpack; the introduction of Fiona Volpe (Luciana Paluzzi), a rare Bond villainess who doesn’t fall under 007’s spell; the sheer, lush spectacle of the Bahamas setting.

But it is also a film that is too in love with itself. The underwater battles, so innovative at the time, drag on for so long that they become an endurance test. The final sequence aboard Largo’s yacht, Disco Volante, is chaos, with sped-up film and awkward cuts that feel rushed, mismatched with the deliberate pacing of everything that came before.

If Goldfinger was the moment Bond became Bond, Thunderball was when the formula began calcifying. It is the first Bond film that feels overproduced, overlong, overindulgent. It is, in many ways, a victim of its own success.

And yet, something is fascinating about it. It is a film that sits at the precipice of two eras: the lean, sharp thrillers of early Bond, and the bloated extravaganzas that would define the Roger Moore years. It is Bond at his peak, and Bond just beginning to lose his way.

Would I recommend Thunderball? Of course. It is still a Bond film, still a piece of cinematic history, still a spectacle worth experiencing. But if I had to choose between this and its unofficial remake, Never Say Never Again, I might just opt for the latter. Sometimes, the off-brand version understands the assignment even better than the original.