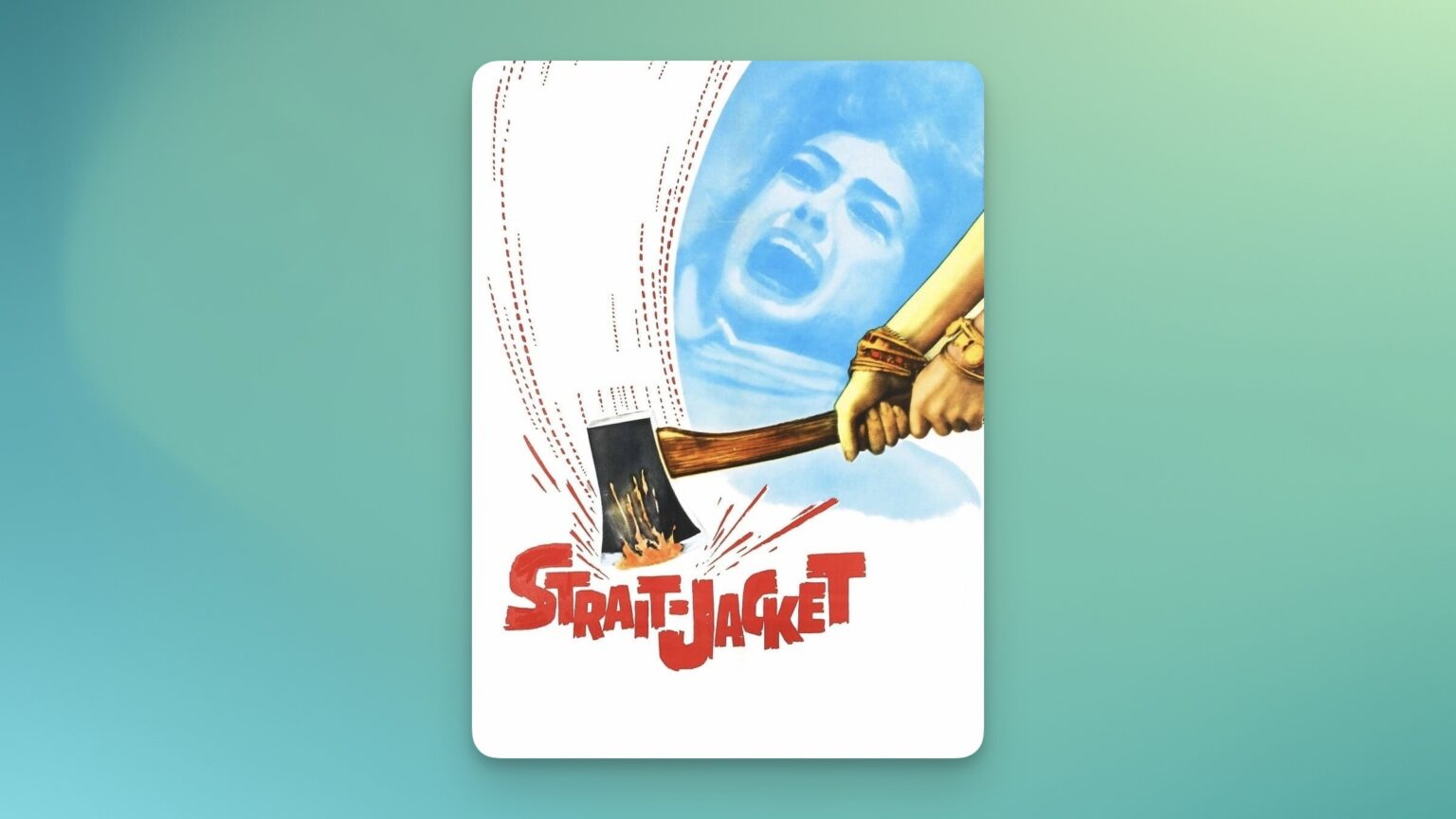

In 1964, Joan Crawford picked up an axe.

Not metaphorically—though one could argue that every great Hollywood reinvention is its own kind of execution—but literally. There she was, an Academy Award-winning actress, a legend of Old Hollywood glamour, standing in front of William Castle’s B-movie lens, ready to swing.

The result was Strait-Jacket, a film that, at first glance, seems like just another lurid horror flick. A woman with a violent past is released from a psychiatric institution. Murders begin anew. Suspicion swirls. The whole thing has the structure of a classic pulp thriller, the kind of thing you might expect from Robert Bloch, the man who wrote Psycho. But beneath the surface, Strait-Jacket is doing something else—something more subversive, more unsettling. It’s a film about identity, about reinvention, and about whether we can ever truly escape the roles that society—and history—assign to us.

To understand Strait-Jacket, you have to understand Crawford. By 1964, she was no longer the ingenue of Grand Hotel or the wronged housewife of Mildred Pierce. She was something else entirely: an actress who had outlived her own era, a woman who had survived Hollywood’s cruel cycle of discarding its leading ladies. And in Strait-Jacket, she weaponized that history.

Her character, Lucy Harbin, is a woman trying to outrun her past. Twenty years earlier, she murdered her husband and his lover in a fit of rage. Now, she’s released from a psychiatric institution, attempting to reconnect with her daughter, Carol (Diane Baker). But the past doesn’t let go so easily. Carol encourages her mother to reclaim the glamorous image she had at the time of the murders—curling her hair into tight black ringlets, applying the same youthful makeup. It’s an eerie echo of Hollywood’s obsession with forcing women to remain frozen in time.

And then, of course, the killings begin again.

The brilliance of Strait-Jacket isn’t just in its jump scares or its Grand Guignol excess (though the flying prosthetic heads certainly add to the experience). It’s in the way it plays with perception. At first, it seems obvious: Lucy, fragile and unstable, must be the one responsible for the new wave of murders. But the film slowly reveals a darker truth—Carol, the devoted daughter, has been orchestrating everything.

This is where Strait-Jacket becomes a study in psychological manipulation. Carol makes her doubt her own sanity. She isolates her, plants evidence, subtly reinforces the idea that Lucy is losing her grip on reality. Today, we’d call this gaslighting. In 1964, it was simply an exercise in power.

Watching Strait-Jacket now, in an era where plot twists are expected, the film’s final revelation still holds up. Maybe it’s because the groundwork is laid so carefully—Carol’s control over her mother is there from the beginning, but we don’t want to see it. Maybe it’s because of Crawford’s performance, which walks the tightrope between melodrama and genuine vulnerability. Or maybe it’s because the film taps into the fear that the people we love might not be who they claim to be.

Strait-Jacket is not a perfect movie. It leans into its B-movie roots, reveling in its campy excesses. That’s part of its charm. It understands the spectacle of horror, the way fear is as much about performance as it is about violence. At its center is Crawford, an actress who knew better than anyone that reinvention is both a necessity and a curse.