Endora, Iowa. Population: 1,091 (and falling). A place where the air hangs thick with the scent of stagnation, where dreams evaporate like the morning mist, and where the only thing moving faster than the rust creeping up the water tower is the relentless march of time. This is the suffocating backdrop against which Lasse Hallström’s What’s Eating Gilbert Grape unfolds, a film less about a specific question and more about the quiet desperation of existing in a world that feels too small.

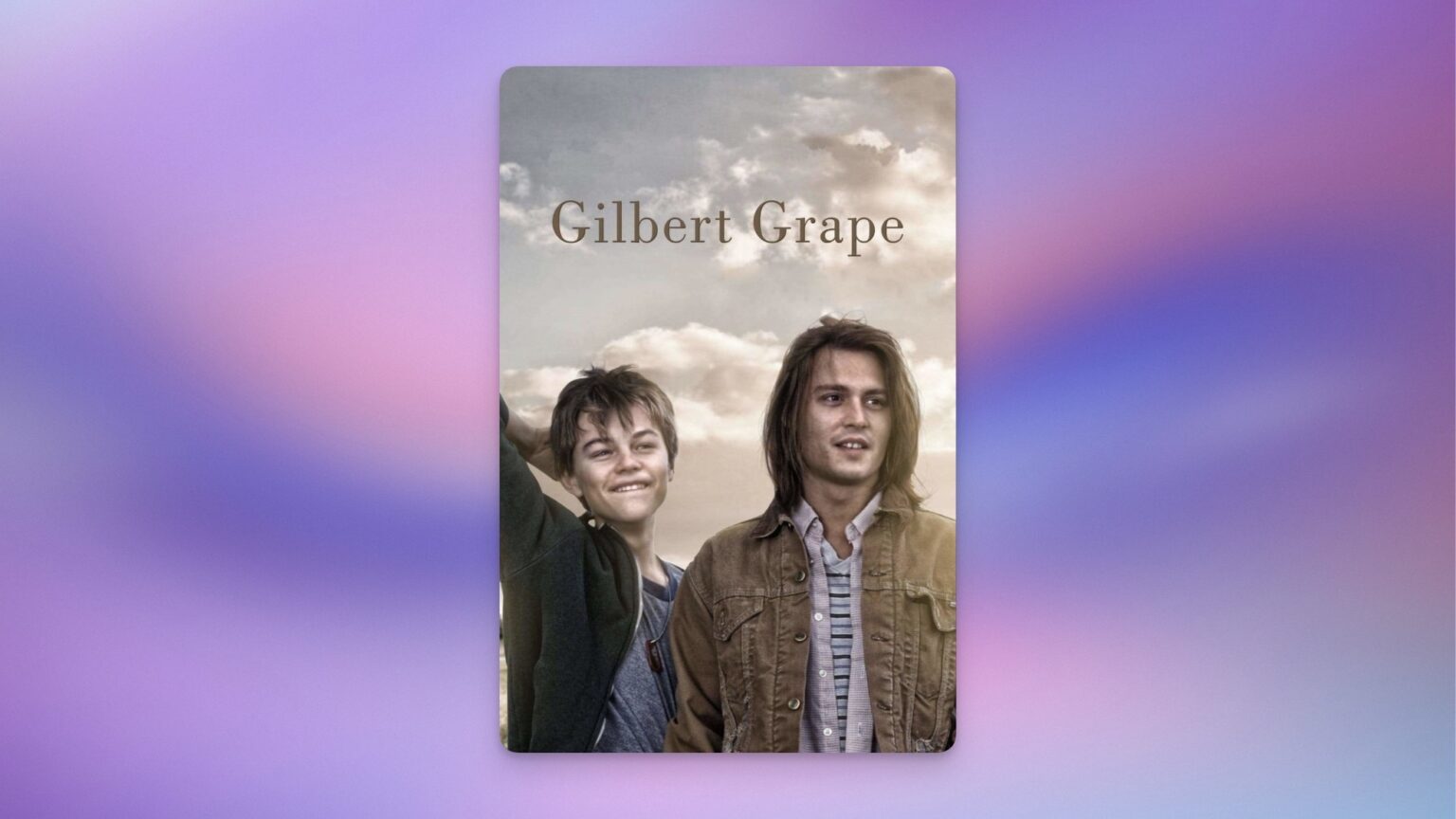

Let’s be clear: this isn’t a film of grand pronouncements or explosive plot twists. It’s a film of whispers and glances, of unspoken anxieties etched onto Johnny Depp’s perpetually furrowed brow as Gilbert, the titular character burdened by the weight of his family. Depp, in a performance of remarkable restraint, embodies the exhaustion of a young man trapped by circumstance, his every sigh a testament to the crushing responsibility he shoulders.

And then there’s Arnie, played with breathtaking authenticity by a young Leonardo DiCaprio. It’s a performance that transcends mere acting; it’s an inhabitation, a channeling of a spirit so pure and vulnerable it leaves you breathless. The fact that DiCaprio didn’t receive an Oscar for this role remains a cinematic injustice, a testament perhaps to the Academy’s frequent blindness to genuine artistry. Arnie’s precarious dance with the world, his fascination with heights and water, his childlike glee and sudden, terrifying meltdowns, are all rendered with a heartbreaking realism that lingers long after the credits roll.

Darlene Cates, in her only film role, delivers a performance as Mama that is as astonishing as it is affecting. Her physical presence, amplified by astute costuming and hair design, becomes a symbol of the family’s immobility, a literal and metaphorical weight holding them down. Yet, within this immobility, Cates manages to convey a flicker of humanity, a glimmer of the woman she once was before grief and circumstance consumed her.

The film’s suspense, masterfully crafted by screenwriter Peter Hedges, doesn’t rely on cheap thrills or jump scares. It’s the slow-burn suspense of a life lived on the precipice, the constant fear of Arnie’s next climb, Mama’s next fall, the ever-present threat of the family’s fragile ecosystem collapsing. The scene where Arnie scales the water tower is a masterclass in tension, a visceral representation of Arnie’s yearning for escape mirrored by Gilbert’s own desperate desire to break free.

The ending, much debated, offers not a definitive answer but a glimmer of hope. Gilbert and Arnie driving off in Becky’s van, a vehicle not broken down like so many other things in Endora, feels less like an ambiguous departure and more like a decisive act of liberation. It’s a deliberate contrast to the opening scenes, where Gilbert watches the endless stream of cars passing through, representing the life he craves. The ceremonial burning of the house, with Mama’s body inside, is not an act of cruelty but a necessary catharsis, a symbolic severing of the ties that bind them to their suffocating past. They are not simply leaving a town; they are leaving behind a life.

While the setting is undeniably bleak, What’s Eating Gilbert Grape is not a depressing film. It’s a film about the enduring power of love and resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity. It’s a film about the small moments of grace that illuminate even the darkest corners of our existence. It’s a film that, like Becky’s presence in Gilbert’s life, reminds us that even in the most desolate of landscapes, there is always the possibility of connection, of hope, of a life beyond the confines of our own Endora.