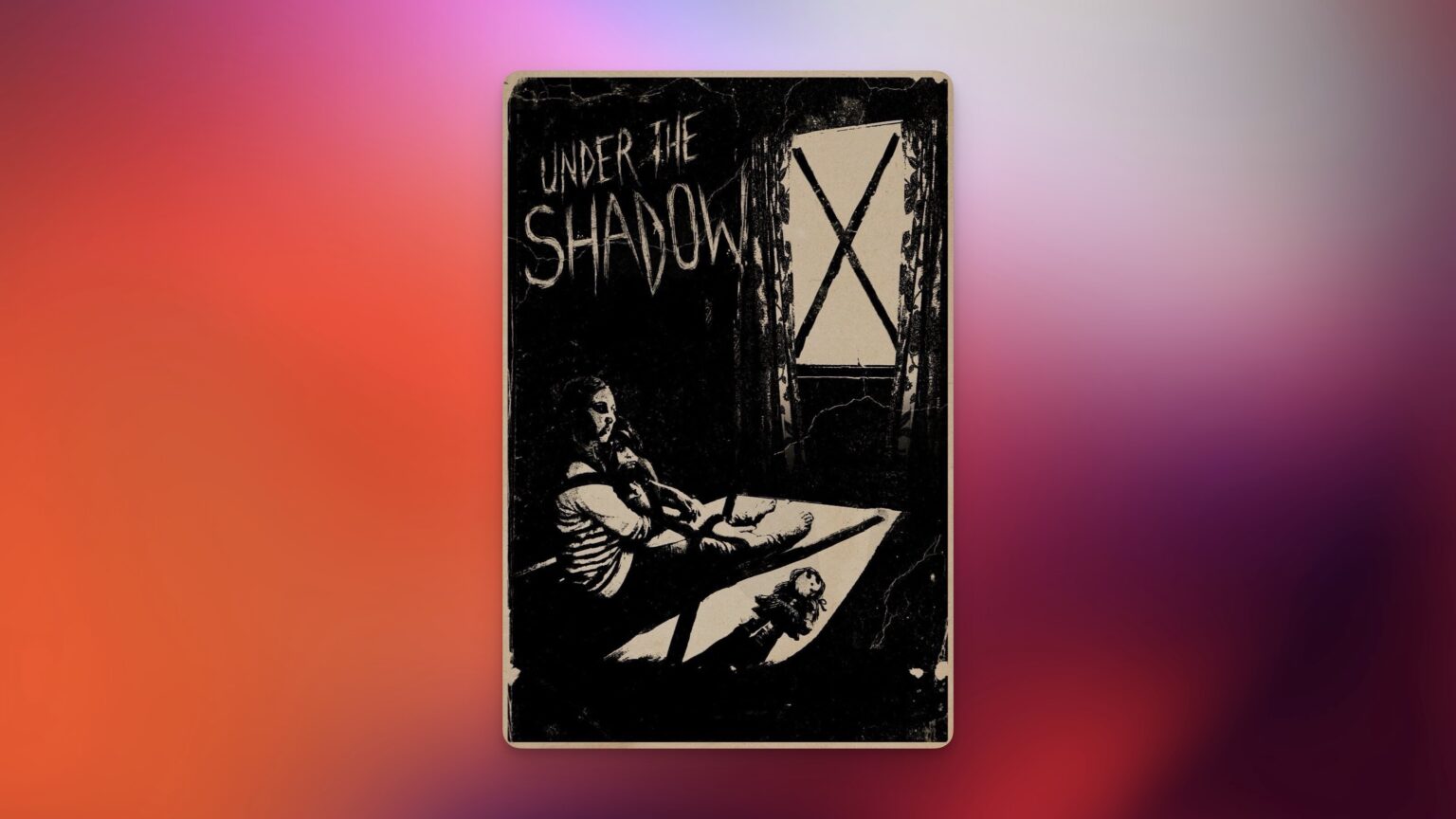

Under the Shadow is a howl. It’s a primal scream against the suffocating condemnations placed upon women, a scream muffled by the dusty, bomb-ridden streets of Tehran. The film burrows under your skin, not with cheap jump scares but with the slow, creeping dread of a life constantly under siege.

It’s not just a djinn scratching at the ceiling. It’s the djinn of war, tearing apart a country and tearing apart families. It’s the djinn of patriarchy, whispering insidious doubts in Shideh’s ear, telling her she’s not good enough, not pious enough, not motherly enough. And yes, it’s the djinn of the unseen, the uncanny, the thing that rustles in the dark when you’re most vulnerable. This film understands that the truest horrors are often the ones we can’t name, the ones that fester in the silences.

Narges Rashidi embodies this struggle with breathtaking vulnerability. We see Shideh’s desperation, the way she clings to her forbidden Jane Fonda workout tapes like a lifeline, a desperate gasp for a self the regime wants to erase. We see the way her eyes dart nervously around the apartment, searching for an escape that doesn’t exist. She’s a woman trapped, not just by a malevolent spirit, but by a society that seeks to define her solely as wife and mother.

The visuals, for crying out loud, the visuals! The djinn, a swirling vortex of shadow and fabric, an insistent reminder of the unseen forces that seek to control Shideh. The way it slithers through cracks in the ceiling, a metaphor, perhaps, for the cracks in Shideh’s own carefully constructed facade. And that scene under the sheet… a battle for identity, a war fought in the intimate, suffocating space of a marital bed, a space where women are so often expected to surrender their own desires, their own ambitions.

But the film is messy. The djinn’s connection to the missile feels convenient at best. A symbol of the destructive power of war, but a symbol that lacks the visceral punch of the film’s more intimate horrors. And Mehdi, poor, sidelined Mehdi. His “avatar” experience feels tacked on, a missed opportunity to explore the psychological toll of war on men.

And that “test” scene. It chills me to the bone. Is it a moment of madness? A supernatural manipulation? Or is it a glimpse into the dark, primal fear that lurks in every mother’s heart, the fear of failing to protect her child? The film doesn’t offer easy answers, and that’s naturally its greatest strength and weakness. It leaves us with questions, with unease, with the lingering sense that the true horrors are the ones we carry in ourselves.

I mean, also bombs, though.

★★★★☆🧡