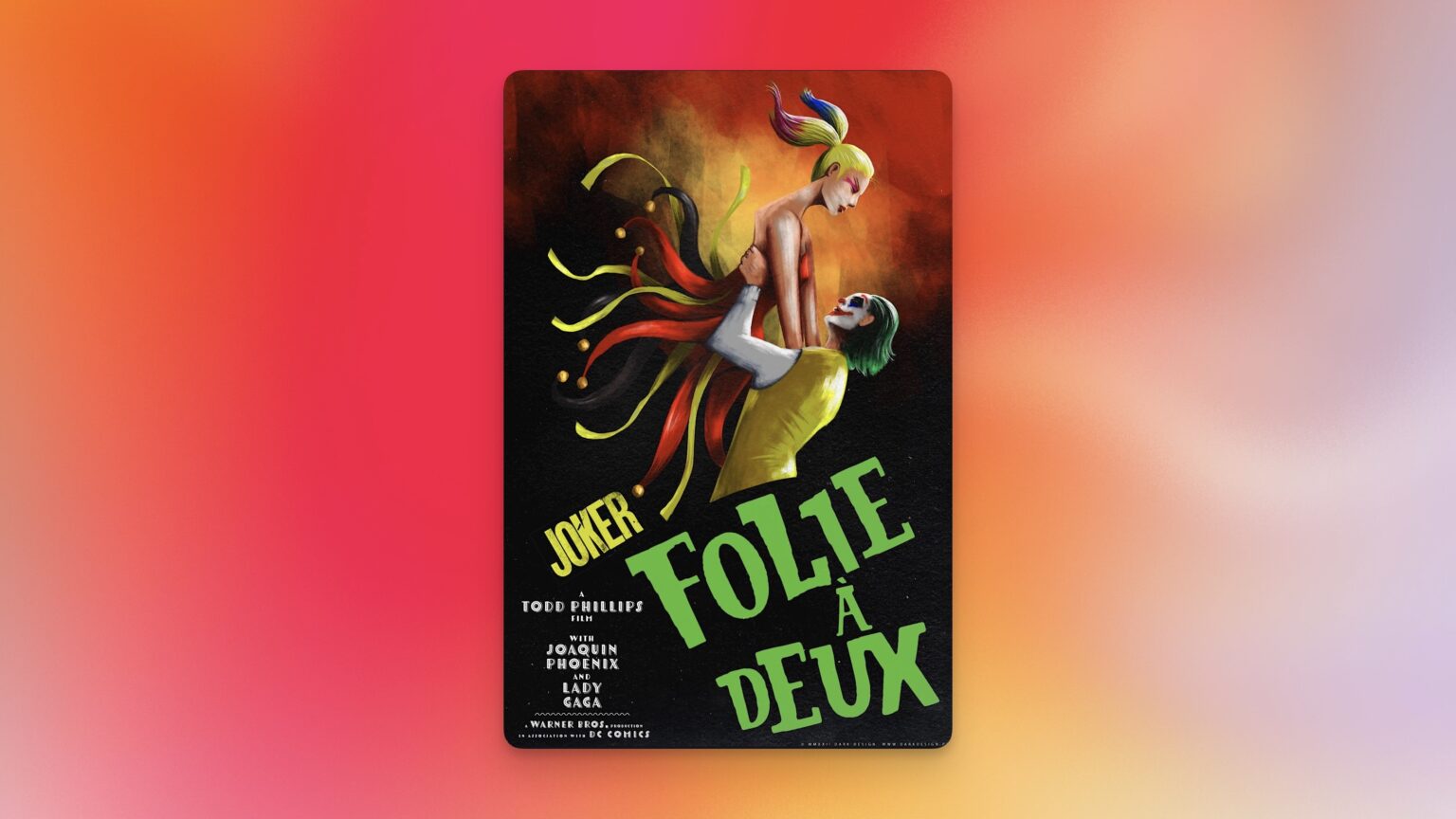

This film, this Folie à Deux, it’s a peculiar beast. A glittering, unsettling thing, like a shard of glass embedded in a velvet glove. It lures you in with the promise of spectacle, of Joaquin Phoenix’s raw, visceral performance – a performance so compelling it almost makes you forget the monstrous nature of the character he inhabits. And the camera, oh the camera! Lawrence Sher, the cinematographer, paints with light and shadow, capturing the textures of decay, the grotesque beauty of a face contorted in laughter or rage. Every pore, every fleck of makeup, is rendered with a precision that borders on the obsessive. It’s a feast for the eyes, even as it makes your stomach churn.

Phoenix, of course, is magnificent. He doesn’t just play Arthur Fleck, he is Arthur Fleck, inhabiting the character’s brokenness with a ferocity that’s both terrifying and mesmerizing. There’s no praise for the Joker himself, the man is a void, a black hole of malevolent energy, but Phoenix’s portrayal is a masterclass.

And then there’s the music. The film flirts with the musical genre, offering glimpses of what might have been. There are moments of genuine brilliance, particularly one show-stopping number that finally scratches that Joker itch, a twisted, theatrical expression of his fractured psyche. The concept, using music to explore Arthur’s descent into madness, is intriguing, but the execution feels hesitant, as if the filmmakers were afraid to fully commit to the bit. They dip their toes into the waters of musical theatre, but never fully immerse themselves. A missed opportunity, perhaps.

The film grapples with interesting ideas, particularly the susceptibility of the masses to charismatic figures, regardless of how warped their message might be. This thread, established in Joker, continues here, with the city teetering on the brink of chaos, a reflection of Arthur’s own internal turmoil. The film’s interpretation of the pseudobulbar affect, introduced in the first film, adds another layer of complexity, blurring the lines between genuine emotion and involuntary outbursts. We are left questioning the authenticity of Arthur’s feelings, just as the citizens of Gotham are misled by his chaotic performance.

But here’s the rub: it feels like they filmed the wrong movie. So much of the narrative is bogged down in legal and procedural elements, courtroom dramas and psychiatric evaluations. While the city burns outside, the film keeps us trapped within the confines of a Gotham courtroom and Arkham Hospital. I yearned to see the chaos unfold, to witness the city’s reaction to this asshat of an anti-hero, this criminal clown who has become a symbol of their discontent. Instead, we’re stuck in institutional hallways, listening to legal jargon. And every time the narrative shifted to Harvey Dent, played by a disconcertingly polished Harry Lawtey, the illusion shattered. He looked like he belonged on a yacht with daddy, not in the grimy, corrupt world of Gotham. Even the eventual glimpse of his origin story, intriguing as it was, couldn’t quite redeem the jarring miscasting. Each cut to Dent pulled me out of the film, a stark reminder of the artifice of it all.

And Lady Gaga, a force of nature, a global music icon, is strangely underutilized. Given the film’s musical leanings, her presence felt almost perfunctory. It’s as if the filmmakers didn’t quite know what to do with her talent.

It’s rumored the film cost upward of $150 million. $200 million? More? I’ll be damned, but I can’t figure out how that money was spent on screen.

Now, for the spoilers. That final shot. Joker on the ground, and behind him, a figure emerges from the shadows, the true agent of chaos. It’s a chilling moment, a suggestion that everything we’ve witnessed has been a prelude, a distorted origin story for the Joker we know from the comics. This reframing retroactively improves the first film, transforming it from a standalone character study into the first act of a much larger, more sinister narrative. It feels like a long con, a cinematic sleight of hand, and I, for one, am willing to be fooled. The idea that this was all planned, that the filmmakers knew where they were going all along, is far more satisfying than the alternative. It elevates the entire project, turning it into something far more complex and intriguing than it initially appeared. Even if it’s a lie, it’s a beautiful lie, and I’ll gladly embrace it.

We’re talking about the film on The Film Board this weekend, show released next Tuesday.