When I was a teenager, I wanted to be a spy. You get it, right? The moral ambiguity, the intricate betrayals, the sense that everyone is moving across a board like a chess piece, never quite sure who’s playing them and who’s being played. The best ones—think The Spy Who Came in from the Cold—capture not just the mechanics of espionage but the psychological weight of it. A Dandy in Aspic (1968) wants to be one of those films. At moments, it is. But much like its protagonist, it gets caught somewhere in between, unable to fully commit to its own identity.

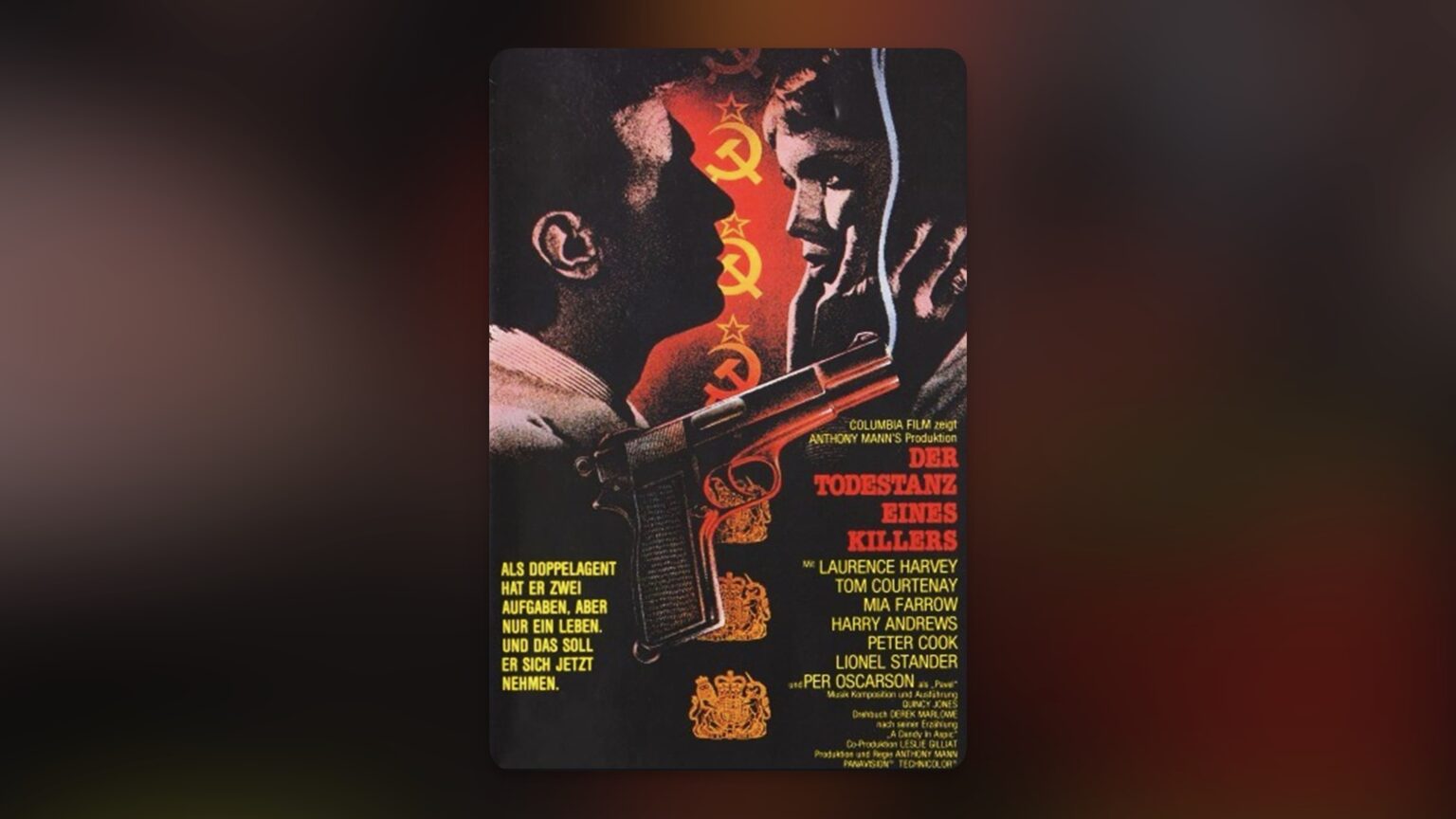

Laurence Harvey plays Eberlin, a British spy who is, in fact, a Russian double agent. When his superiors task him with hunting down a KGB operative named Krasnevin, the twist is immediate and cruel—he is Krasnevin. It’s a brilliant setup, a perfect existential trap that should ratchet up the tension with every passing scene. But instead of squeezing the audience in a vice, the film lets the suspense slip through its greasy fingers.

Harvey—who also took over directing duties after Anthony Mann’s death—delivers a performance that feels appropriately weary, but perhaps too much so. Eberlin moves through the film like a man who has already resigned himself to his fate. He’s supposed to be unraveling, but instead, he seems like he started the film already undone.

Mia Farrow’s Caroline is a free-spirited photographer who flits in and out of the story. She’s meant to be a contrast to Eberlin—a symbol of life beyond the cold, gray world of espionage—but she never quite fits. Her relationship with Eberlin is underdeveloped, her motivations unclear. She’s always there, but for what purpose? Even the film doesn’t seem to know.

The central issue for me is that A Dandy in Aspic is a film divided against itself. It wants to be a cerebral spy thriller, but it also wants moments of swinging-sixties cool. It wants to be a slow-burn character study, but it also wants bursts of action. The result is a film that never quite settles its rhythm.

Tom Courtenay is terrific as Gatiss, the British agent increasingly suspicious of Eberlin. He’s cold and precise with a sense that he enjoys the game a lot more than he should. The film’s opening sequence—featuring a marionette being violently shaken—is a striking metaphor for the spy’s lack of control over fate. And Quincy Jones’s score, while undeniably of its time, adds a layer of tension that the script often fails to generate.

But the film’s production woes are evident. Mann’s death left a gap that Harvey, for all his talents, wasn’t quite able to fill. Where does that leave A Dandy in Aspic? It’s not a disaster. It’s not a hidden gem. It’s a film with a stellar premise, a strong supporting cast, and some genuinely compelling moments—but also one that ultimately fails its potential. Maybe in the hands of a more assured or consistent director, it could have been a classic. As it stands, it’s a fascinating misfire—interesting, occasionally gripping, but ultimately frustrating.