There’s a frame in The Pit and the Pendulum when Vincent Price, all wide eyes and trembling hands, finally lets go of the last thread of his sanity. He straightens, lowers his voice, and suddenly starts speaking as if he were his father, Sebastian Medina, the ruthless torturer of the Spanish Inquisition. It’s a sharp turn, a classic Corman twist—except by the time it happens, I found myself less intrigued and more impatient.

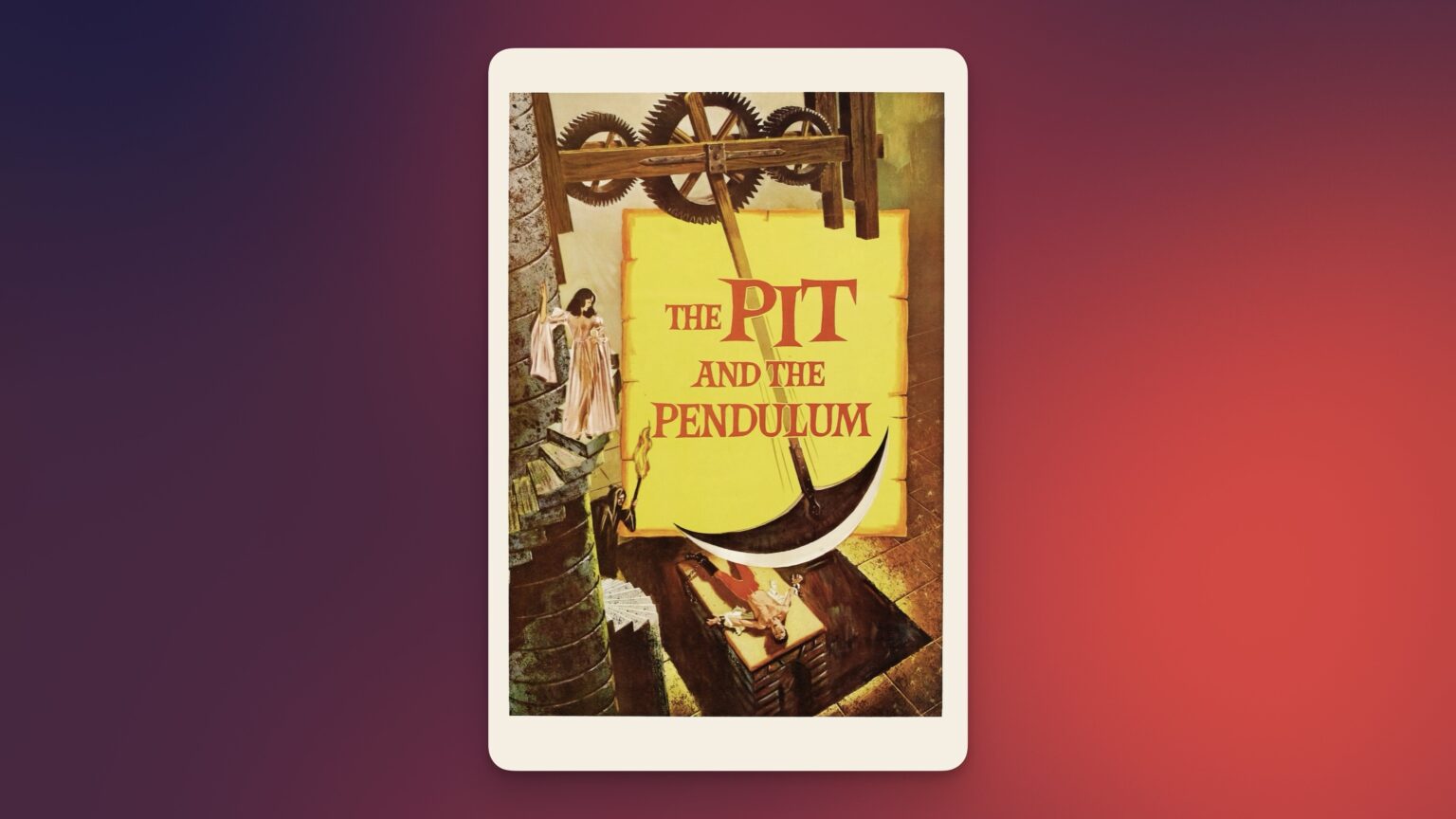

Roger Corman’s Poe adaptations have a reputation for being atmospheric, moody, and visually striking despite their low budgets. The Pit and the Pendulum is true to that. While it has flashes of brilliance—particularly in its final act—it takes far too long to get there, and the journey is more tedious than terrifying.

Corman was a master of making movies on the cheap, and sometimes that worked to his advantage. Here, he and production designer Daniel Haller took old Universal set pieces—archways, staircases, gothic decor—and repurposed them into a sprawling 16th-century Spanish castle. The result is a setting that looks impressive at first glance but, after a while, starts to feel like exactly what it is: a collection of borrowed parts.

Visually, the film leans heavily into its gothic atmosphere, with deep shadows, eerie corridors, and the occasional surreal color-drenched flashback. But while cinematographer Floyd Crosby does his best to elevate the material, the film’s pacing undercuts its effectiveness. Scenes drag. Conversations repeat the same ominous warnings. The tension, instead of building, stagnates.

If there’s one reason to watch The Pit and the Pendulum, it’s Vincent Price. He knows exactly what kind of movie he’s in and commits fully, delivering a performance that oscillates between quiet anguish and full-blown hysteria.

The problem? He’s the only one delivering.

John Kerr, as the film’s ostensible protagonist, is as wooden as the castle doors, making every scene he’s in feel like an anchor dragging the film down. Barbara Steele, whose eerie presence should have been a major asset, is underused. And the grand reveal lands with a dull thud rather than a shocking blow.

There’s a lot of brooding—so much brooding—and a lot of whispering about family curses with Price staring off into the middle distance. But for a film that’s supposed to be about psychological torment, it never really gets under the skin.

The film’s last twenty minutes are its strongest. The moment Nicholas fully embraces his father’s persona, the movie shifts gears, and suddenly the stakes feel real. The pendulum sequence, in which Francis (Kerr) is strapped to a stone slab as a massive, razor-sharp blade swings ever closer to his chest, is the film’s highlight—and the most successful moment in the film of genuine tension. It’s not saying much. But it’s there.

Here’s the issue: by the time we get there, it feels like too little, too late. The film spends so much time lingering on Nicholas’s guilt and Francis’s investigation that the real horror elements only kick in at the very end. It’s like sitting through an hour of buildup for a five-minute payoff.

At its best, The Pit and the Pendulum is a showcase for Vincent Price’s brand of grand, theatrical horror. At its worst, it’s a sluggish, overlong film that mistakes brooding for suspense. The atmosphere is there. The gothic visuals are there. The ingredients for a great horror film are all present. But the pacing is off, the supporting performances are weak, and the story—despite Matheson’s efforts to expand Poe’s short tale—feels stretched too thin.