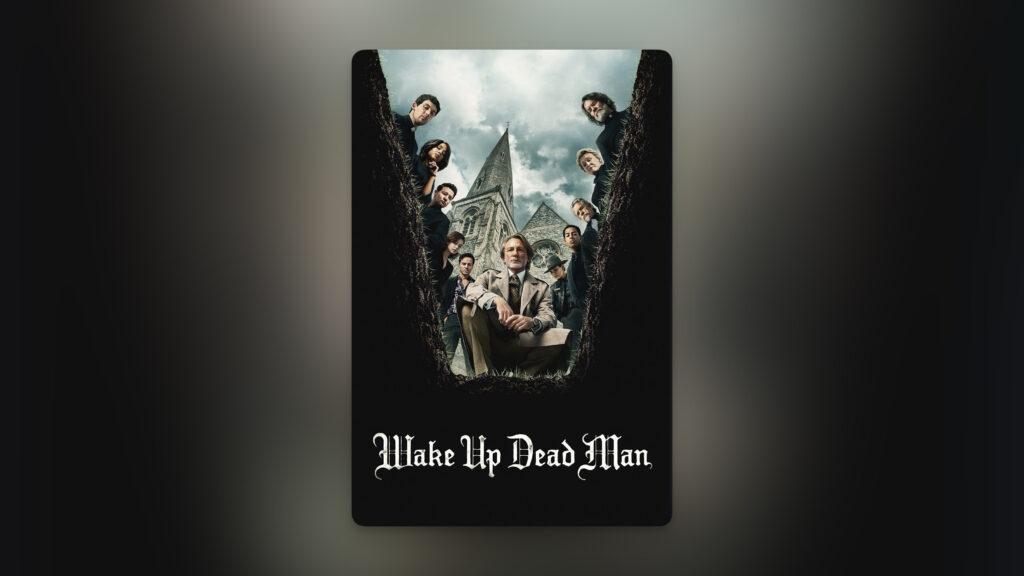

Ryan Johnson’s Wake Up Dead Man opens with an act of violence so theatrically impossible that the film doesn’t even bother hiding it from you. Someone has been stabbed during a Good Friday service in a locked church, and the movie tells you, with its whole chest, that what just happened could not have happened. Then it stands there, arms crossed, daring you to argue.

This is the third Benoit Blanc mystery, and it’s the first one that doesn’t feel like it’s having any fun at all.

That’s not a complaint—it’s an observation about ambition. Where Knives Out skewered generational wealth with a scalpel and Glass Onion took a sledgehammer to tech-bro narcissism, Wake Up Dead Man trades spectacle for something grittier, heavier, and far more unsettling. The locked room isn’t a billionaire’s island or a grand estate. It’s a rural church in the American Northeast, where faith and certainty have been weaponized in equal measure, and where the only thing more dangerous than a knife is the conviction that you’re absolutely right.

Johnson has always been interested in certainty as a narrative device—characters who believe they know exactly what happened, exactly who’s to blame, exactly how the world works. But here, that interest becomes the entire engine of the film. Every character in Wake Up Dead Man is sure of something. Sure of their faith, sure of their inheritance, sure of their righteousness. And Johnson, with the patience of a man who’s built two of these contraptions already, watches them all collide.

I recently covered this film on The Film Board, and what struck me most in that conversation—and what lingers now—is how deliberately Johnson has shifted the register. This isn’t a mystery that delights in its own cleverness the way Glass Onion did. It doesn’t revel in the baroque pleasures of the genre. Instead, it takes the locked-room mystery—one of the most inherently playful structures in all of detective fiction—and uses it to examine something deeply uncomfortable: the way we perform certainty in the face of doubt.

The mechanics of the mystery are deceptively straightforward. A man is killed during a church service. The doors are locked. Everyone inside has an alibi that seems airtight. Benoit Blanc arrives, not with a flourish, but with a quiet, weary curiosity. And then the film spends the next two hours methodically dismantling every assumption you’ve made.

What makes it work—what makes it more than a well-constructed puzzle—is that Johnson refuses to let the mystery exist in a vacuum. The locked church is a pressure cooker for ideology. The Wicks family, with their tangled history of wealth, betrayal, and religious fervor, become avatars for the ways we weaponize belief to justify our worst impulses. And the treasure everyone’s chasing—the inheritance that was promised but never delivered—becomes a metaphor for the American social contract itself: something we’re all told exists, something we’ve built our lives around, something that may never have been real in the first place.

The film’s visual language reinforces this shift in tone. Johnson and cinematographer Steve Yedlin trade the sun-drenched opulence of Glass Onion for something far more austere. The church is beautiful, yes, but it’s a hard beauty—all dark wood and stained glass that filters light into something cold and judgmental. The color palette is muted, almost oppressive. This is a film that looks like it was shot in the exact moment before a storm breaks, and it never quite lets you exhale.

The ensemble cast rises to meet that challenge. Daniel Craig’s Benoit Blanc evolves here into something quieter, more observational—a listener who understands that the real mystery is why everyone is so desperate to believe their version of events. The rest of the cast—an astonishing collection of largely British actors delivering pitch-perfect regional American accents—populate the church with people who feel lived-in, damaged, and terrifyingly certain of themselves.

There’s a moment midway through the film where Cy Draven, played with ugly precision by Daryl McCormack, delivers what might be the thesis statement of the entire piece. He’s talking about politics, about the machinery of modern American discourse, and he says something to the effect of: Show people something they hate. Tell them it’s going to take away something they love. It’s a line that could easily feel too on-the-nose, too didactic. But in context, surrounded by people who have spent their entire lives doing exactly that to each other, it lands with the weight of inevitability.

This is what Johnson is doing with the locked-room mystery. He’s showing us a structure we love—the intricate puzzle, the impossible crime, the brilliant detective who sees what no one else can—and then using it to interrogate the very certainty that makes such stories satisfying. We want Blanc to tell us what happened. We want the mystery solved. We want the moral universe of the story to snap back into place. But Wake Up Dead Man keeps asking: what if certainty itself is the real crime?

Does it work? Mostly, yes. The film’s willingness to sit in discomfort, to let scenes breathe and characters contradict themselves, is one of its greatest strengths. But it’s also, at times, a liability. The final act—particularly the last twenty minutes—feels like Johnson struggling to land a plane he’s been flying at cruising altitude for too long. The revelations keep coming, each one peeling back another layer, and while the mystery itself resolves satisfyingly, the film doesn’t quite know when to stop talking.

This is the risk of making a mystery that’s more interested in commentary than catharsis. Johnson has built a machine that runs on ambiguity, on the tension between what we believe and what we can prove. But the genre demands resolution. And so the film gives it to us—but not in the way you’d expect. Blanc, in a remarkable choice, refuses to solve it himself. He hands the story to Martha to tell, recognizing that she must own this revelation. The pieces fall into place, but the lingering discomfort doesn’t dissipate. The certainty the film critiques doesn’t evaporate just because the mystery is solved.

In a strange way, that’s what makes Wake Up Dead Man the most interesting entry in the series so far. It’s a film that understands the locked-room mystery as a fundamentally conservative form—a puzzle that exists to be solved, a chaos that exists to be ordered—and then uses that form to examine a moment in American life where order feels increasingly out of reach.

There’s a scene where Jud sits down to write a letter, and Blanc sits, drinking bourbon by the fire as he does. His narration overlays time we’ve already experienced, and Johnson—in a typically elegant touch—has the act of writing take exactly one hour of screen time, matching the hour of storytelling we’ve just watched. It’s the kind of structural playfulness that reminds you Johnson is still having fun with form, even as the subject matter grows heavier.

But what makes this moment more than clever is what it reveals about the film’s deeper project. Johnson has always been fascinated by the gap between what people say and what they do, between the stories we tell ourselves and the truths we can’t face. Wake Up Dead Man takes that fascination and builds an entire mystery around it. It’s a film that refuses to let anyone—not the characters, not the audience, not even Benoit Blanc himself—rest easy in their assumptions.

Is it the most audacious Knives Out mystery yet? Perhaps. It’s certainly the one most willing to risk alienating its audience in service of its argument. But it’s also the one that feels most urgent, most necessary. In a cultural moment defined by performative certainty and weaponized belief, Johnson has made a mystery that asks us to sit with our doubt. That’s a harder trick to pull off than any locked-room puzzle, and the fact that he mostly succeeds is a testament to his skill as both a storyteller and a diagnostician of our current ailments.

I walked away from Wake Up Dead Man convinced of two things: first, that Ryan Johnson is one of the most vital filmmakers working today, and second, that I want more of these. Not because they’re easy or comforting—this one is decidedly neither—but because they’re necessary. They remind us that the hardest mysteries to solve aren’t the ones with impossible alibis and hidden clues. They’re the ones where everyone is absolutely certain they’re right, and no one can prove it.